CRITICAL EXAMINATION AND REFUTATION

OF THE CHIEF COUNTER-SCHEMES OF APOCALYPTIC INTERPRETATION; AND ALSO OF

DR. ARNOLD’S GENERAL PROPHETIC COUNTER-THEORY

IT

was stated at the conclusion of my Sketch of the History of Apocalyptic

Interpretation, that there are at present two, and but two, grand

general counter-Schemes to what may be called the historic Protestant

view of the Apocalypse: that view which regards the prophecy as a

prefiguration of the great events that were to happen in the Church, and

world connected with it, from St. John’s time to the consummation;

including specially the establishment of the Popedom, and reign of Papal

Rome, as in some way or other the fulfilment of the types of the

Apocalyptic Beast and Babylon. The first of these two counter-Schemes is

the præterists’ which would have the prophecy stop altogether short of

the Popedom, explaining it of the catastrophes, one or both, of the

Jewish Nation and Pagan Rome; and of which there are two sufficiently

distinct varieties: the second the Futurists’; which in its original

form would have it all shoot over the head of the Popedom into times yet

future; and refer simply to the events that are immediately to precede,

or to accompany, Christ’s second Advent; or, in its various modified

forms, have them for its chief subject. I shall in this second Part of

my Appendix proceed successively to examine these two, or rather four,

anti-Protestant counter-Schemes; and show, if I mistake not, the

palpable untenableness alike of one and all. Which done,1 it may perhaps

be well, from respect to his venerated name, to add an examination of

the late Dr. Arnold’s general prophetic counter-theory. This together

with a notice of certain recent counter-views on the Millienniem, will

complete our review of counter-prophetic Schemes.

Now with regard to the Præterist Scheme, on the review of which we are

first to enter, it may be remembered that I stated it to have had its

origin with the Jesuit Alcasar:1 and that it was: subsequently, and

after Grotius’ and Hammond’s prior adoption a of it adapted and improved

by Bossuet, the great Papal champion, under one form and modification;2

then afterwards, under another modification by Hernnschneider, Eichhorn,

and others of the German critical and generally infidel school of the

last half-century;3 followed in our own æra by Heinrichs, and by Moses

Stuart of the United States of America.4 The two modification as appear

to have arisen mainly out of the differences of date assigned to the

Apocalypse; whether about the end of Nero’s reign or Domitian’s.5 I

shall I think, pretty well exhaust whatever can be thought to call for

examination in the system, by considering separately first the Neronic,

or favourite German form and modification of the Præterist Scheme, as

propounded by Eichhorn. Hug. Heinricks, and Moses Stuart; secondly

Bossuet’s Domitianic form the one most generally approved, I believe, by

Roman Catholics.

CHAPTER I

§ 1. EXAMINATION AND REFUTATION OF THE GERMAN NEGOSIC PRÆTERIST

APOCALYPTIC COUNTERCHEME

The reader has already been made acquainted with the main common

features of this German form of the Præterist Apocalyptic Scheme.6

Differing on points of detail yet with the exception that Hartwig and

Herder pretty much confine themselves to the Jewish catastrophe, and

Ewald, Bleek, and De Wette to that of heathen Rome1) it may generally be

described as embracing both catastrophes: the fall of Judaism being

signified under that of Jerusalem, the fall of Heathenism under that of

Rome; the one as drawn out in symbol from Apoc. 6 to 11 inclusive, the

other from Apoc. 12 to 19: whereupon comes thirdly, in Apoc. 20, a

figuration of the triumph of Christianity. So, with certain differences,

Hernnschncider, Eiehhorn, Hug, Heinrichs, &c., in Germany;2 M. Stuart in

America; and, in England, Dr. Davidson.3—In my review of the Scheme each

of these two historic catastrophes, as supposed Apocalyptically figured,

will of course furnish matter for critical examination; not without

reference to the Apocalyptic date also, as in fact essentially mixt up

with the historic question.—But, before entering on them, I think it may

be well to premise a notice,

1st, on THE GENERALLY VAGUE LOOSE PRINCIPLE OF PROPHETIC INTERPRETATION

professedly followed by the Præterists.

Considering the self-sufficient dogmatism which pre-eminently

characterizes the School in question, even as if, à priori to

examination; all other schemes were to be deemed totally wrong, and the

Præterist Scheme alone conformable to the discoveries and requirements

of “modrn exegesis,”4 (a dogmatism the more remarkable, when exhibited

by a man of calm temperament and unimpassioned style, like Professor

Stuart,5 and which to certain weaker minds may seem imposing,) the

question is sure to arise, What the grounds of this strange

presumptuousness of tone? What the new and overpowering evidence in

favour of the modern Præterists? What the discovery of such unthought of

coincidence between the prophecy on the one hand, and certain facts of

their chosen Neronic æra on the other, as to settle the Apocalyptic

controversy in their favour, at once and for ever? And then the surprise

is increased by finding that not only has no such discovery been made,

not only no such discovery been even pretended to, but that in fact they

put it forward, as the very boast of the Præterist system, that

coincidences exact and particular are not to be sought or thought of:

that the three main ideas about the three cities, or three antagonist

religions represented by them, so as above mentioned, are pretty much

all that there is of fact to be unfolded; and that, with certain

exceptions, (of which exceptions more in a later part of this review,)

all else is to be regarded as but the poetic drapery and ornament.1—Now

in mere rationalists of the School, like Eichhorn and many others, men

professedly disbelieving the inspiration of the Apocalypse, all this is

quite natural and consistent: seeing that its author wrote, they take

for granted, as a mere dramatist and poet; and, as to details, what the

limit ever assigned to a poet’s fancy, except as his own taste or

critical judgment might impose one? But that Christian expositors, like

Professor Stuart and Dr. Davidson, men professing to believe in St.

John’s inspiration as a prophet, (and to these I here chiefly refer,)

should deliberately so pronounce on the matter, so resolve even what

seems most specific into generalizations,1 and what seems stated as fact

into mere poetic drapery, will appear probably to my readers, as to

myself, most astonishing.

It is of course due to these writers to mark by what process of thought

they arrive at this conclusion; and on what principle, or by what

reasons, they have justified it to themselves. And, passing by the

negative argument from the discrepancy and unsatisfactoriness of the

historic detailed interpretations given by expositors who seek in the

Apocalypse a prophetic “epitome of the eivil and ecclesiastical history

of Christendom,” (as to which, wherever justly objected to, the remark

was obvious that further research might very possibly supply what was

wanting, and rectify what was unsatisfactory, so as I hope has been done

on various points in the present Commentary,2) passing this, I say, the

intended use and object of the Apocalypse, at the presumed time of its

writing, will be found to have been that which mainly guided the learned

American Professor to the true principle of exegesis, (as he designates

it,) whereby to interpret the Book.1 For, argues he, during a

persecution like Nero’s, (this being his supposed date of the

Apocalypse,) when the Church was “bleeding at every pore,”2 how could it

take interest in information as to what was to happen in distant ages,

(excepting of course the final triumph of Christianity,) or indeed as to

anything but what concerned their own immediate age and pressure,

whether in Judea or at Rome? Hence then to this the subject-matter of

the Apocalypse must be regarded as confined.3 And whereas, on this

exegetic hypothesis, scarce anything appears in the actual historic

facts of the particular period or catastrophe in question, which can be

considered as answering to the prophetic figurations in detail,

therefore all idea of any such detailed and particular intent and

meaning in these prophetic figurations must be set aside; and they must

be regarded as the mere drapery and ornament of a poetic Epopee, albeit

by one inspired. As a Scriptural precedent and justification for this

generalizing view of the Apocalyptic imagery, Psalm 18, which was

David’s song after his deliverance from Saul, and Isaiah 13, 14, on the

fall of Babylon, (the former more especially,) are referred to, and

insisted on, by the learned Professor.

But (reserving the subject of the Apocalyptic date for a remark or two

presently under my next head of argument) let me beg here to ask, with

reference to the very limited use and object so assigned to the

Apocalyptic prophecy,—as if only or chiefly meant for the Christians

then living, by them to be understood, and by them applied in the way of

encouragement and comfort, as announcing the issue of the trials in

which they were then personally engaged,—what right has Professor Stuart

thus to limit it? Was it not accordant with the character of God’s

revelations, as communicated previously in Scripture, (especially in

Daniel’s prophecies, which are of all others the most nearly parallel

with the Apocalypse,) to foreshow the future in its continuity from the

time when the prophecy was given, even to the consummation: and this,

not with the mere present object of comforting his servants then living,

but for a perpetual witness to his truth; to be understood only

partially, it might be, for generations, but fully in God’s own

appointed time? So, for example, in the Old Testament prophecies

concerning Christ’s first advent; prophecies which not only the Old

Testament Jews, but even the disciples of Christ, understood most

imperfectly, till Christ himself, after he had actually come, explained

them: and so again in Daniel’s prophecies extending to the time of the

end; which, until that time of the end, were expressly ordered to be

sealed up.1—And then, next, what historic evidence have we of Christians

of Nero’s time having so understood the Apocalypse, as the American

Professor would have it that they must have done?2 Not a vestige of

testimony exists to the fact of such an understanding; albeit quite

general, according to him, among the more intelligent in the Christian

body. On the contrary, the early testimony of Irenæus, disciple to

Polycarp, who was himself disciple to St. John, indicates a then totally

different view of the Apocalyptic Beast from Professor Stuart’s, as if

the only one ever known to have been received: a view referring it, not

to any previous persecution by Nero and the Roman Empire under him, but

to an Antichrist even then future; one that was to arise and persecute

the Church not till the breaking up, and reconstruction in another form,

of the old Empire.—Moreover the whole that our Professor would have to

be shown by the Apocalypse, viz. the assured triumph of Christianity

over both Judaism and Paganism,—I say this, instead of being any new

revelation specially suited to cheer the Christians of the time, had

been communicated in part by Daniel, in part by Christ himself, much

more fully and particularly long before.1 As to the Professor’s grand

precedent of Psalm 18, urged again and again in justification of his

explaining away nearly all the more particular symbolizations of the

Apocalypse, as if mere poetic drapery and ornament, is the parallel a

real one, or the argument from it valid? Says the Professor;2 See,

though the subject of the Psalm be at the heading declared to be David’s

deliverance from Saul, yet under what varied imagery this is set

forth:—how, in depicting them, David makes the earth to shake and

tremble, and the smoke to go forth from God’s nostrils, and his

thunderings to be heard in the heaven, and his lightnings shot forth to

discomfort the enemy: all mere poetical ornament; not particular

circumstantial fact; much less fact in chronological order and

development. But, let me ask, does the Psalmist profess, as his very

object, to tell the facts that had occurred in the period of David’s

suffering from Saul, so as the Apocalyptic revealing Angel does to tell

the things of the coming future?3 Or with any such orderly division, and

arrangement for chronological development of facts, as in the singularly

artificial Apocalyptic division into its three septenaries of Seals,

Trumpets, and Vials, (each of the latter subordinate evidently to the

former,) and the various chronological periods so carefully interwoven?

Again, as to the symbolizations in the Psalm, is Professor Stuart quite

sure that they refer only to David and Saul; and that David is not

carried forward in the Spirit, beyond his own times and his own

experience, to picture forth the future triumphs of a greater David over

a greater Saul; triumphs not to be accomplished in fine without very

awful elemental convulsions, and the visible and glorious interposition

of the Almighty? Surely what is said in verse 43, of his (the chief

intended David’s) “being made the head of the heathen,” tells with

sufficient clearness that such is indeed the true exegesis of the Psalm:

and so most expositors of repute, I believe, explain it.—If the testing

is to be by a real parallel, let Daniel’s orderly prophecies of the

quadripartite image and the four Beasts be resorted to, to settle the

question of exegesis. Is all there figured relative only to Daniel’s own

time; and all else mere poetic ornament and drapery?

So much on the general exegetic principles of the German Præterist

School. Let me now proceed,

IIndly, to consider these Præterists’ HISTORICAL SOLUTION, including

especially the two grand catastrophes laid down by them, as the two main

particulars unfolded in the Apocalypse; and show, as I trust, both in

respect of the one and the other, the many and indubitable marks of

error stamped upon it.

Of course the Neronic date is an essential preliminary to this Scheme,

in the minds of all Præterist expositors who, like M. Stuart and Dr.

Davidson, admit the apostolicity and inspiration of the Book. And, as I

venture to think that I have in my 1st Volume completely proved that the

true date is Domitianic, agreeably with Irenæus’ testimony, not Neronic

or Galbaic,1 that single fact may in such case be of itself deemed

conclusive against the theory.—Nor, let me add, in case of non-infidel

Præterists only. For the very strong opinion as to the sublimity and

surpassing æsthetic beauty of the Apocalypse admitted by the German

Neologians, Eichhorn inclusive, as the result of the Semlerian

controversy, compared with the utter inferiority of all Church writers

of the nearest later date, does even on rationalistic principles almost

involve the inference of St. John’s authorship; especially as coupled

with the fact of the Apocalyptic writer’s assumption of authority over

the Asiatic Bishops he addrest, and the air of truth, holiness, and

honesty that all through mark his character. Which admitted, and also,

as by Eichhorn, the Domitianic as the true date, even a rationalist like

him must, I think, be prepared to admit the high improbability of such a

writer making pretence to prophesy a certain catastrophe about Nero and

Rome, and another certain catastrophe about Jerusalem, as if things then

future, when in fact the one had happened 30, the other 25 years before.

Whence the baselessness, even on rationalistic principles, of the whole

Neronic Præterist Scheme.—But we will now proceed more in detail to the

examination of the two catastrophes separately.

1. And, 1st, as to the catastrophe of Judaism and Jerusalem, depicted in

the figurations from Apoc. 6 to 11 inclusive.

Argues Professor Stuart, as abstracted in brief, thus:1 “It is for some

considerable time not unfolded who the enemy is against whom the rider

of the white horse in the first Seal has gone forth conquering, followed

by his agencies of war, famine,2 and pestilence; him against whom the

cry is raised of the Christian martyrs slain under the 5th Seal, and the

revolution of whose political state is evidently the subject of Seal the

sixth. But in Apoc. 7 the enemy meant is intimated. For when it is

stated that 144,000 are sealed, by way of protection, out of all the

tribes of Israel, meaning evidently those that have been converted from

among the Jews to Christianity, it follows clearly that it is the

unsealed ones of those tribes, or unconverted Jews, forming the great

body of Israel, that are the destined objects of destruction. A view

this quite confirmed in Apoc. 11; where the inner temple is measured, as

that which is not to be ejected: this meaning, that whatever was

spiritual in the Jewish religion was to be preserved in Christianity;3

while the rest, or mere external parts of the system, as well as the

Holy City Jerusalem itself, was to be abandoned and trodden down.” So

substantially Professor Stuart: and so too his prototype Eichhorn, and

his English follower Dr. Davidson. This is the strength of their first

Part; the details of Seals and Trumpets being of course little more in

this system than intimations of something awful attending or impending,

altogether general; or indeed, perhaps, mere “poetic drapery and

costume.” Let us then try its strength where it professes to be

strongest.

The enemy to be destroyed, it is said, was shown to be the Jews: because

it was the Jewish tribes (all but the sealed few from out of them) that

were to have the tempests of the four winds let loose on them; and

because it was the Jewish temple (all but the inner and measured part of

it) that was to be abandoned to the Gentiles. Let us test this

conclusion by the threefold test of what is shown, first, as to the

intent of the Jewish symbolic scenery elsewhere in the Apocalypse;

secondly, as to the religious profession of the people actually

destroyed in the Trumpet-judgments; thirdly, as to the intended people’s

previous murder of Christ’s two Witnesses, in their thereupon doomed

city.

As to the first, already in the opening vision a chamber as of the

Jewish temple had been revealed; with seven candlesticks like those in

the old Jewish temple,1 and one in the High Priest’s robing that walked

among them. Was its signification then Jewish or Christian; of Judaism

or Christianity? We are not left to conjecture. The High Priest was

distinctively the Christian High Priest, Christ Jesus; the seven

candlesticks the seven Christian Churches. This explanation at the

outset is most important to mark; being the fittest key surely to the

intent of all that occurs on the scene afterwards of similar

imagery.—Further, in Seal 5 a temple like the Jewish, at least the

temple-court with its great brazen altar, is again noted as figured on

the scene. Now we might anticipate pretty confidently, from the

previously given key just alluded to, that the temple was here too

symbolic of the Christian worship and religion, not the Jewish. But

there is, over and above this, independent internal evidence to affix to

it the same meaning. For the souls under the altar, who confessedly

depict Christian martyrs, appear there of course as sacrifices offered

on that altar; their place being where the ashes of the Jewish

altar-sacrifices were gathered. Which being so, could the altar mean

that of the literal Judaism; and the vision signify that the Jews,

zealous for their law, and thinking to do God service, had there slain

the Christian martyrs, as if heretics? Certainly not; because on their

altar the Jews never offered human sacrifices, and would indeed have

esteemed it a pollution. Therefore we have independent internal evidence

that the Jewish temple and altar, figured on the Apocalyptic scene, had

here too a Christian meaning; depicting (as both St. Paul, and Polycarp

after him, so beautifully applied the figure) the Christian’s willing

sacrifice of himself and his life for Christ.2—Further in Apoc. 8 the

temple is again spoken of as apparent; with its brazen sacrificial altar

in the altar-court, its golden incense-altar within the temple proper,

and one too, habited as a Priest, who received and offered incense,

according to the ceremony of the Jewish ritual. Was this meant literally

of Jewish incense and Jewish worship? Assuredly not. For the incense of

the offering priest is declared to be “the prayers of all the saints;”

i. e. as all admit,1 of Christians distinctively from literal

Jews.—Again, with reference even to the temple figuration in Apoc. 11:2,

which furnishes his chief Jewish proof-text, our Professor himself

admits, nay argues, that the inner and most characteristic part of it

(the same that was measured by St. John) signified that spiritual part

of Judaism which was to be preserved in Christianity, as contrasted with

the mere externals of Jewish ritualism:2 thus construing it, not

literally, with reference to the worship of the national Israel, but

symbolically, with reference to that of the Christian Israel:3 albeit

with no little mixture of what is erroneous, and consequently confused

and inconsistent in his reasoning.4—All which being so, what, I ask,

must by the plainest requirements of consistency and common sense

follow, but that as the offerers of Jewish worship in the Jewish temple,

depicted on the Apocalyptic scene, meant in fact Christians, so they

that are called Jews or Israelites in the Apocalyptic context must mean

Christians also, at least by profession? A conclusion clenched by the

fact which I have elsewhere urged, that the twelve tribes of God’s

Israel in the New Jerusalem of Apoc. 21 are on all hands admitted to

designate Christians, mainly Gentile Christians; and so surely, in all

fair reasoning, the twelve tribes of Israel mentioned in Apoc. 7 also.

Next, as to the religious profession or character of those that were to

suffer through the plagues of the first great act of the Drama, (or

rather Epopee, as Stuart would prefer to call it,)1 their character is

most distinctly laid down in Apoc. 9:20, as actual idolaters. For it is

there said, “that the rest of the men, which were not killed by these

plagues, yet repented not of the works of their hands, that they should

not worship dæmons, and idols of gold, and silver, and brass, and stone,

and wood:”—a description so diametrically opposed to the character of

the Jews in Nero’s time, and ever afterwards, that one would have

thought with Bossuet,2 and indeed Ewald too,3 that it settled the point,

if anything could settle it, that Jews were not the parties meant. And

how then do the German Præterists, that take the Judaic view, overcome

the difficulty? Few and brief are the words of Eichhorn’s

paraphrase:—“It means that they persevered in that same obstinate mind,

which once showed itself in the worship of idols!”1 says M. Stuart:2 “In

the Old Testament Jews that acted in a heathenish way were called

heathens: and moreover in the New Testament covetousness is called

idolatry: and moreover in the time of Herod theatres, and other such

like heathen customs, had become common in Judea.”3 But surely such

observations, when put forward in explanation of the descriptive clause

that spoke of men “worshipping idols of gold, and silver, and brass, and

stone, and wood,” must be felt to be rather an appeal ad misericordiam

in the Expositor’s difficulty, than an argument for the fitness of the

descriptive clause, to suit the Jews of the times of Nero and Vespasian:

especially when coming from one who is led elsewhere in his comment to

state (and state most truly) that the Jews were ready, one and all,

rather to submit their necks to the Roman soldiers’ swords, than to

admit an image that was to be worshipped within their city.4 Indeed it

is notorious that they regarded images altogether as abominations; and

that the Roman attempts at erecting them more than once nearly caused

desperate rebellions.—As for Dr. Davidson, he here exhibits more at

least of discretion than the American Professor. He passes over the

difficulty, as if re desperatâ, in dead silence.

Try we, thirdly, the Judaic theory of our German Præterists by the test

of the Witness-slaying prophecy, including the place, time, and author

of their slaughter.—This is put forth as one of the strongest points in

the Judaic part of their view: it being stated to occur in the city

“where their Lord was crucified;” i.e., say the Præterists, in

Jerusalem. But first, we ask, what witnesses? “The Jewish chief priests

Ananus and Jesus,” answer Herder and Eichhorn; “mercilessly massacred,

as Josephus tells us, by the Zealots.”5 But how so? Must they not rather

be Christ’s witnesses, exclaims Stuart;6 (since it is said, “I will give

power to my witnesses;”) and therefore Christians? Of course they must.

Which being so, the next question is, Who then the notable Christians

that Stuart considers to have been slain in Jerusalem, in the witness

character, at this epoch; i. e. during the Romans’ invasion of Judea?

Does he not himself repeat to us the well-known story on record, that

the Christians forthwith fled to Pella, agreeably with their Lord’s

warning and direction, so soon as they saw the Romans approach to

beleaguer Jerusalem? “But,” says he in reply, “can we imagine that all

would be able to make their escape? Would there not be sick and aged and

paupers to delay the flight; and faithful teachers too of Christianity,

that would choose to remain, to preach repentance and faith to their

countrymen? These I regard as symbolized by the two “Witnesses:”1 and

these therefore as answering in their history at this crisis to St.

John’s extraordinary and circumstantial prediction, about the Witnesses’

testimony, miracles, death, resurrection, ascension. But what the

historic testimony to support his view? Alas! none! absolutely none! In

apology for this total and most unfortunate silence of history he

exclaims; “The Jew Josephus is not the historian of Christians; and

early ecclesiastical historians have perished:” adding however, as if

sufficient to justify his hypothesis; “But Christ intimates, in his

prophecy of the destruction of Jerusalem, that there would be

persecution of Christians at the period in question.” A statement quite

unjustified (if he means persecution to death in Jerusalem, and at the

time of the siege) by the passages he refers to.2 Does not Christ say,

“Not a hair of your heads shall perish?” At last he condescends to this:

“At all events it is clear that the Zealots, and other Jews, did not

lose their disposition to persecute at this period!!”3 Such is the

impotent conclusion of Professor Moses Stuart: such the best explanation

he can devise, on his hypothesis, of the wonderful Apocalyptic prophecy

respecting the Witnesses.—Nor is his need supplied by Dr. Davidson.

“Notwithstanding God’s long-suffering mercy,” says this latter, “the

Jews continue to persecute the faithful witnesses.” This, I can assure

the Header, is the sum total of his observations on the point before

us.4—Nor is it here only that the Judaic part of the Præterist Scheme,

applied to the Witness-story in the Apocalypse, breaks down. For,

further, the city where the Witnesses’ corpses were to be exposed is

declared to be the city the great one;1 that which is the emphatic title

of the seven-hilled Babylon or Rome, in the Apocalypse; never of

Jerusalem.2 (How it might be Rome, and yet the city where the Lord Jesus

had been crucified, the Reader has long since seen!3)—Nor this alone.

For the Beast that was to slay them was το θηριον το αναβαινον εκ της

αβυσσου, the Beast that was to rise from the abyss;4 a Beast which

(especially with the distinctive article prefixed so as here to it)

cannot but mean one and the same with that which is mentioned under

precisely the same designation in Apoc. 17:8;5 and there, as all the

Præterists themselves allow, designates a power associated some way with

Rome. And what Stuart’s explanation? Why, that it means in Apoc. 11

simply Satan!6—Indeed alike the declared fact of the witness-slaying,

and of the great city as the place of their slaughter, and of the Beast

from the abyss as their slayer, (as also, let me add, the period of the

1260 days, assigned alike to the Witnesses’ sackcloth-prophesying first,

and to the Beast’s reign afterwards,) do so interweave the first half of

the Apocalyptic prophecy, from Apoc. 6 to 11, with the part subsequent,

that, as to any such total separation, in respect to subject, of the one

from the other, as the Præterists urge, on their hypothesis of a double

catastrophe, it is, I am well persuaded, and will be so found by one and

all who attempt to work it out, an absolute impossibility.

I might add yet a word as to the ill agreeing times of the supposed

Jewish catastrophe and the Roman; the former being in the Præterist

Scheme first set forth, and the Roman figured afterwards: whereas the

chronological order of the two events was in fact just the reverse; the

Roman persecution of Christians, and quickly consequent fall of Nero,

preceding the fall of Jerusalem. But the argument (which indeed might be

spared ex abundanti) will occur again, and somewhat more strikingly,

under our next Head.—To this let us then now pass onwards; and consider,

as proposed,

2ndly, the German Præterists’ second grand division of the Apocalypse,

and second grand catastrophe; viz. that affecting Pagan Rome.

And here, as before, I shall not stop at minor points; but hasten

rapidly to that which is considered by the Præterists as their strongest

ground.—It is to be understood that they generally make Apoc. 12

retrogressive in its chronology to Christ’s birth, and the Devil’s

primary attempts to destroy both him, and his religion, and his early

Church in Judea; though in vain. Then, after note of the Dragon’s

dejection from his former eminence, and the song, “Now is come

salvation, &c.,” we arrive at the Woman’s flight into the wilderness,

meaning they say the Church’s flight to Pella, on the Romans advancing

to besiege Jerusalem: some outbreak of Jewish persecution at the time

(the same under which the Witnesses were to fall within Jerusalem)

answering probably1 to the floods from the Dragon’s mouth; and the 3½

years, said of the Woman’s time in the wilderness, answering also

sufficiently well to the length, not indeed of the siege, but of the

Jewish war. (Mark, in passing, how the symbolic Woman, first made to be

the Theocratic Church in its Jewish form, travailing with, and bringing

forth Christ,2 has now become, not the Church Catholic, which in Nero’s

time had indeed spread over the Roman world, but the little Section of

it which remained stationary in Judea!)—Then the Dragon, being enraged

at the Woman, “went away to make war with the remainder of her seed, who

keep the commandments of God, and hold fast the testimony of Jesus.”

That is, enraged that the Jews, his original instrument of persecution,

should be destroyed and fail him, he leaves the Jewish scene of his

former operations, and goes elsewhere, to stir up a new persecutor

against Christians in Nero.—But did not Nero’s persecution occur before

the Jews’ destruction? No doubt! The anachronism is honestly admitted by

Professor Stuart.1 An anachronism the more remarkable, because he makes

the vision of the 144,000 in Apoc. 14 to be a vision of encouragement to

Christians, suffering under Nero’s persecution; depicting as it did,

according to him, the Christian Jews occupying Jerusalem as a now

Christian city:2 an event this which could not have happened till

Jerusalem’s destruction, about four years after the commencement of

Nero’s persecution; and did not in fact take place till some years

later.3 “But in an Epopee, like the Apocalypse,” says Stuart, “we are

surely not bound to the rigid rules of a book of Annals!”

Thus then we come to consider Apoc. 13 the Chapter on the Beast; and,

connectedly with it, (for it does not need to dwell on the intervening

Chapters,)5 the further explanatory symbolizations about the Beast in

Apoc. 17,

Behold us then now before the very citadel of the German Præterists!

“And see,” they say, “how impregnable it is! For not only is the Woman

that rides the Beast expressly stated to be the seven-hilled imperial

city Rome, so that the Beast ridden must be the persecuting Roman

Empire; but the time intended is also fixed. For it is said that the

Beast’s seven heads, besides figuring seven hills, figured also seven

kings, or rather eight: of whom five had fallen at the time of the

vision; which must mean the five first emperors, Julius, Augustus,

Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius; and one, the sixth, was; which of course

must be the nest after Claudius, i. e. Nero. Nay, to make the thing

clearer, the Beast’s name and number 666 are specified; or, as some

copies read, 616. And so it is that in Hebrew נֶרוֹן קֵסַר, Neron Cæsar,

has the value in numbers of 666, which is one frequent Rabbinical way of

writing Nero’s name; or, “if the Hebrew be that of Nero Cæsar, without

the final n, then it gives the number 616.”

No doubt the numeral coincidence is worthy of note, and the whole case,

so put, quite plausible enough to call for examination. It is indeed

obvious to say, as to the name and numeral, that a Greek solution would

be preferable to one in Hebrew; and a single name to a double one:

principles these recognized, as we have seen, by Irenæus, and all the

other early Fathers that commented on the topic.2 But in this there is

of course nothing decisive. A graver objection seems to me however to

lie against the suggested numeral solution, in that a part of the name

being official,—I mean the word Cæsar,—this agnomen, though fitly

applicable to Nero while the reigning emperor, would hardly be

applicable to him when resuscitated after his death-wound, and so become

the Beast of Apoc. 13 of whom the name was predicated. But this involves

inquiry into the Beast’s heads; to which inquiry, as the decisive one,

let us now therefore at once pass on.

The heads then, as they assert, mean certain individual kings. This is

not surely according to the precedent of Daniel 7:6, where the third

Beast’s four heads would seem from Dan. 8:8 to have signified the

monarchical successions that governed the four kingdoms into which

Alexander’s empire was divided at his death.—But, not to stop at this,

the decisive question next recurs, What the eighth head of the Beast, on

this hypothesis of the Præterists: Nero being the sixth; and, as they

generally say, Galba, who reigned but a short time, the seventh? It is

admitted (and common sense itself forces the admission) that this eighth

head is the same which is said in Apoc. 13:3, 12, 14, “to have had a

wound with a sword and to have revived:” and it is this revived head, or

Beast under it, (let my Readers well mark this,1) that is the subject of

all the prophecy concerning the first Beast in Apoc. 13 and all

concerning the Beast ridden by the Woman in Apoc. 17, What then, we ask,

this eighth head of the Beast? And, in reply, first Eichhorn, and then

his copyists Heinrichs, Stuart, Davidson, all four refer us to a rumour

prevalent in Nero’s time, and believed by many, that after suffering

some reverse he would return again to power: a rumour which after his

death took the form that he would revive again, and reappear, and retake

the empire.2 Such is their explanation. The eighth head of the Beast is

the imaginary revived Nero.—But do they not explain the Beast (the

revived Beast) in Apoc. 13 and his blasphemies, and persecution of the

saints, and predicated continuance 42 months, of the real original Nero,

and his blasphemies and his three or four years’ persecution of the

Christians, begun November, 64, A.D. and ended with Nero’s death, June

9, A.D. 68? Such indeed is the case; and by this palpable

self-contradiction, (one which however they cannot do without,) they

give to their own solution its death-wound: as much its death-wound, I

may say, as that given to the Beast itself to which the solution

relates.

So that really, as regards the truth of the solution concerned, it is

needless to go further. Nor shall I stop to expose sundry other

absurdities that might easily be shown to attach to it: e. g. the

supposed figuration of the fall of the Pagan Roman empire in the fall of

the individual emperor Nero, albeit succeeded by Pagan emperors like

himself.3—But I cannot feel it right to conclude my critical examination

of the system without a remark as to something on this head far graver,

and more to be reprobated, than any mere expository error, however gross

or obvious. The reader will have observed that as well Prof. Stuart and

Dr. Davidson, as the German Eichhorn, explain the repeated direct

statements, “The Beast had a wound with the sword, and lived,” “The

Beast that thou sawest is not, and shall be, and is to ascend from the

abyss,” &c. &c., to be simply allusions to a rumour current in Nero’s

time, but which in fact was an altogether false rumour. That is, they

make St. John tell a direct lie: and tell it, with all the most flagrant

aggravation that fancy itself can suppose to attach to a lie; viz. under

the form of a solemn prophecy received from heaven! Now of Eichhorn, and

others of the same German rationalistic school of theology, we must

admit that they are here at least open and consistent. Their declared

view of the Apocalypse is as of a mere uninspired poem by an uninspired

poet. So it was but a recognized poetical license in St. John to tell

the falsehood. But that men professing belief in the Christian faith,

and in the divine inspiration as well as apostolic origin of this Book,

should so represent the matter, is surely as surprising as lamentable.

It is but in fact the topstone-crowning to that explaining away of the

prophetic symbols and statements, as mere epopee, of which I spoke

before,1 as characteristic of the system. And how does it show the

danger of Christian men indulging in long and friendly familiarity with

infidel writings! For not only are the Scriptural expository principles

and views of Christian men and Neologists so essentially different, that

it is impossible for their new wine to be put into our old bottles,

without the bottles bursting; but the receiver himself is led too often

heedlessly to sip of the poison, and bethinks him not that death is in

the cup.

§ 2. EXAMINATION OF BOSSUET’S DOMITIANIC OR CHIEF ROMAN CATHOLIC

PRÆTERIST, APOCALYPTIC SCHEME

It may probably at once strike the reflective reader that if the

chronology of Bossuet’s scheme, extending as it does from Domitian’s

time to the fall of the Roman empire in the 5th century, do in regard of

the supposed Roman catastrophe abundantly better suit with historic fact

than the German Neronic or Galbaic Præterist Scheme, it is on the other

hand quite as much at disadvantage in respect of the other, or Jewish

catastrophe. For surely that catastrophe was effected in the destruction

of Jerusalem by Titus, above 20 years before Bossuet’s Domitianic date

of the Apocalypse: and all that past afterwards under Hadrian was a mere

rider to the great catastrophe.

But to details. And here at the outset Bossuet’s vague generalizing

views of the five first Seals meet us; as if really little more than the

preliminary introduction on the scene of the chief dramatis personæ, or

agents, afterwards to appear in action; viz. Christ the conqueror, War,

Famine, Pestilence, Christian Martyrs: followed in the 6th by a

preliminary representation, still as general, of the impending double,

or rather treble catastrophe, that would involve Christ’s enemies;

whether Jews, Romans, or those that would be destroyed at the last day.

A view this that even Bossuet’s most ardent disciples will, I am sure,

admit to be one not worth detaining us even a moment: seeing that, from

its professedly generalizing character, the whole figuration might just

as well be explained by Protestants with reference to the overthrow of

one kind of enemy, as by Romanists of another.—Nor indeed is there

anything more distinctive in his Trumpets: with which, however, he tells

us, there is to begin the particular development of events. For, having

settled that the Israelitish Tribes mentioned in Apoc. 7 mean the Jews

literally, (the 144,000 being the Christian converts out of them,) and

so furnish indication that they are parties concerned in what follows in

the figurations, (though the temple, all the while prominent in vision,

is both in the 5th Seal before, and in the figuration of the Witnesses

afterwards, construed by Bossuet, not of the literal Jewish temple, but

of the Christian Church,) he coops up these Jews, and all that is to be

developed respecting them, within the four first Trumpets:—the

hail-storm of Trumpet 1 being Trajan’s victory over them; the burning

mountain of Trumpet 2 Adrian’s victories; (why the one or the other, or

the one more than the other, does not appear;) the falling star of

Trumpet 3 figuring their false prophet Barchochebas, “Son of a star,”

who stirred up the Jews to war; (of course however before the war with

Adrian, signified in the preceding vision, not after it;) and the

obscuration of the third part of sun, moon, and stars, in Trumpet 4,

indicating not any national catastrophe or extinction, but the partial

obscuration of the scriptural light before enjoyed by the Jews, through

Akiba’s Rabbinic School then instituted, and the publication of the

Talmud. As if forsooth the light of Scripture had shone full upon them

previously: and not been long before quenched by their own unbelief;

even as St. Paul tells us that the veil was upon their hearts. Did

Bossuet really believe in the absurdity that he has thus given us for an

Apocalyptic explanation?—In concluding however at this point with the

Jews, and turning to Rome Pagan as the subject of the following

symbolizations, he acts at any rate as a reasonable man; giving this

very sufficient reason for the transition, that they who were to suffer

under the plagues of the 5th and 6th Trumpets are marked in Apoc. 9:20

as idol-worshippers, which certainly the Jews were not. A palpable

distinctive this which, but for stubborn fact contradicting our

supposition,1 one might surely have thought that no interpreter of this,

or of any other Apocalyptic School, would have had the hardihood even to

attempt to set aside. Only does not the statement about the unslain

remnant’s non-repenting of them imply that the slain part had previously

been guilty of the self same sins of idolatry?

So, passing now to the heathen Romans, with reference to their history

in the times following on Barchochebas and the Talmud, the

scorpion-locusts of Trumpet 5 are made by our Expositor to mean

poisonous Judaizing heresies, which then infected the Christian Church:

(Was it not “a piece of waggery” in Bossuet, exclaims Moses Stuart,1 so

to explain it?) Trumpet 6, somewhat better, the loosing of the

Euphratean Persians under Sapor, that defeated and took prisoner the

emperor Valerian; though it is to be remarked that Valerian was the

aggressor in the war, not Sapor, and his defeat in Mesopotamia some way

beyond the Euphrates.—.All which of course offers no more pretensions to

real evidence than what went before: indeed, its total want of anything

like even the semblance of evidence makes it wearisome to notice it. Yet

it is by no means unimportant with reference to the point in hand; for

it shows, even to demonstration, the utter impossibility of making

anything of the Seals and Trumpets on Bossuet’s Scheme.—Let us then

hasten to what both he and his disciples consider to constitute the real

strength of his Apocalyptic Exposition: viz. his interpretation of the

Beast from the abyss, with its seven heads and ten horns, and of the

Woman riding on it: as symbolizations respectively of the Pagan Roman

Emperors, and Pagan Rome.

The notices of this Beast occur successively in Apoc. 11, 13, and 17.

First, in Apoc. 11 the Beast is mentioned passingly and anticipatively,

as the Beast from the abyss, the slayer of Christ’s two witnesses. Next,

in Apoc. 13 it appears figured oil the scene as the Dragon’s successor,

bearing seven heads and ten horns; (one head excised with the sword, but

healed;) another Beast, two-horned, accompanying it, as its associate

and minister; and its name and number being further noted as 666. Once

more, in Apoc. 17, it appears with a Woman, declared to be Rome, seated

on it: and sundry mysteries are then expounded by the Angel, about its

seven heads and ten horns.

Now then for Bossuet’s explanation. This Beast, says he, is the Roman

Pagan Empire, at the time of the great Diocletian persecution; its seven

heads being the seven emperors engaged in that persecution, or in the

Licinian persecution, its speedy sequel: viz. first, Diocletian,

Galerius, Maximian, Constantius; then, Maxentius, Maximin, and Licinius.

Of which seven “five had fallen” at the time of the vision; “one was,”

viz. Maximin; another “had not yet come,” viz. Licinius; and the eighth,

“which was of the seven,” was Maximian resuming the emperorship after he

had abdicated. As to the name and number, it was Diocles Augustus; which

in Latin gives precisely the number 666. Further, the revived Beast of

Apoc. 13 (revived after the fatal sword-wound of the head that was)

figured the emperor Julian; and the second Beast, with two lamblike

horns, the Pagan Platonic priests of the time, that supported him: the

stated time of whose reign, 42 months, was simply a term of time

borrowed from the duration of the reign of the persecutor Antiochus

Epiphanes; signifying that it would, like his, have fixed limits, and be

short.—With regard to the ten horns that gave their power to the Beast,

these signified the Gothic neighbouring powers; which for a while

ministered to Imperial Rome, by furnishing soldiers and joining

alliance; but which were soon destined to tear and desolate the Woman

Rome; as they did in the great Gothic invasions, beginning with Alaric,

ending with Totilas. At the time of which last Gothic ravager, Rome’s

desolation answered strikingly to the picture of desolated Babylon in

Apoc. 18—As to the Woman riding the Beast, the very fact of her being

called a harlot, not an adulteress, showed that it must mean heathen,

not Christian Rome.

Such is in brief Bossuet’s explanation. Now as regards both the first

Beast, and the second Beast, and the Woman too, let it be marked how

utterly it fails; and this is not in one particular only, but in

multitudes.

Thus as to the first Beast.—1. The seven heads, he says, were the seven

persecutors of the Diocletianic æra. But the emperor Severus, Galerius’

colleague and co-persecutor, as Bossuet admits, is arbitrarily omitted

by him, simply in order not to exceed the seven. 2. The Beast from the

abyss, being the Beast that kills the Witnesses, is made in Apoc. 11 to

be the Empire under Diocletian: whereas in Apoc. 17, the Beast from the

abyss (and the distinctive article precludes the idea of two such

Beasts) is explained of a head that was to come after the head that then

was; this latter being Maximin, himself posterior to Diocletian. 3. The

head that was wounded with the sword being, according to Bossuet, the

sixth head “that was,” or Maximin, its healing ought to have been in the

next head in order, that is Licinius. But, this not suiting, he

oversteps Licinius; and explains the healed head of one much later,

Julian. 4. The Beast with the healed head being Julian, the subject of

the description in Apoc. 13 the Beast’s name and number ought of course

to be the name and number of Julian. But no solution suitable to this

striking him, Bossuet makes it Diocles Augustus; the name of the Beast

under a head long previous. 5. As to this name, Diocles Augustus, it is

not only in Latin numerals, which on every account are objectionable,

and which no early patristic expositor ever thought of;1 but, in point

of fact, is a conjunction of two such titles as never co-existed;

Diocletian being never called Diocles when emperor, i. e. when

Augustus.2 6. The Beast “that was, and is not, and is to go into

perdition,” being “the eighth, yet one of the seven,” Bossuet makes to

be Maximian resuming the empire after his abdication. But the prophetic

statement requires that this eighth should rise up after that “which

was,” viz. Maximin; whereas Maximian’s resumption of the empire was

before Maximin.—7. As to the idea of Julian’s hatred of, and disfavour

to Christianity, answering to what is said in Apoc. 13 of the Beast

under his revived head making war on the saints, and conquering them, it

seems almost too absurd to notice. In proof I need only refer to

Julian’s own tolerating Decree about Christians;3 and the behaviour of

Bossuet’s saints, i. e. of the professing Christians of the time, at

Antioch towards Julian.4—8. The contrast of the Beast’s time of

reigning, viz. 3½ years, with Diocletian’s 10 years and Julian’s 1½,

might be also strongly argued from. But I pass it over cursorily; as

Bossuet confesses to have no explanation to offer of it, except that it

is an allusion to the duration of the persecution of Antiochus

Epiphanes!

So as to the Beast’s heads: and still a similar incongruity strikes one

about the Beast’s horns. Take but two points. First, these horns,

“having received no kingdom as yet,” i. e. at the time of the

Revelation, were to receive authority as kings μιαν ὡραν μετα του

θηριου, “at one time with the Beast.” So the doubtless true reading, and

true rendering, as Bossuet allows. But how then applicable to the kings

of the ten Gothic kingdoms?—kingdoms founded long subsequent to both

Diocletian and Julian; and when the Roman empire under their headships,

(which is Bossuet’s Beast,) had become a thing of the past. To solve the

difficulty, Bossuet waves the magician’s rod; and, without a word of

warning, suddenly makes the Beast to mean something quite different from

what it was before: viz. to be Rome, or the Roman empire, of a later

headship than the 8th, or latest specified. Says he “their kingdoms will

synchronize with the Beast, that is with Rome: because Rome will not all

at once [i.e. not immediately on the Goths’ first attacks, begun about

A.D. 400] have lost its existence, or all its power!”2—Yet, again,

secondly, these horns were with one accord to impart their power and

authority to the Beast; of course after themselves receiving this

authority: i. e. as the context of the verse demonstrates, after

receiving their kingdoms. But how so? Says Bossuet, because of their

giving their men to be soldiers of the Roman armies, and of their

settling as cultivators in the empire, and making alliances with the

Roman emperors. But, as to time, could this be said of the reigns of

Diocletian or Julian, when the Gothic ten kings had received no

authority as kings, in the Apocalyptic sense of the word?3 And, as to

the character of the thing, could it be said of the Gothie settlements

in the empire, when sometimes terrible and destructive, (like that of

the Visi-Goths under Valens) that it was a giving their power with one

accord to the Romans?

Then turn we to the second Beast. And let me here simply ask, How could

Bossuet’s Pagan Philosophers, zealots that blasphemed Christ as the

Galilean, answer to the symbol of a Beast with a lamb-skin covering: the

recognized scriptural emblem under the Old Testament of false prophets

who yet professed to be prophets of the true God;1 under the New

Testament of such as would hypocritically pretend to be Christians?

Once more, as to the Woman. And here, 1. instead of the word πορνη,

harlot, fixing her to be Rome Pagan, so as Bossuet asserts, not

Christian Rome apostatized, it most fitly suits the latter; being

applied in the Septuagint to apostatizing Judah,3 in Matthew to an

unfaithful wife.4 2. What the mystery to make St. John so marvel with a

mighty astonishment, if the emblem meant Rome Pagan?5 Did he not know

Rome Pagan to be a persecutor; know it alike by his own experience, and

that of all his brotherhood? 3. What of the total and eternal

destruction predicated of the Apocalyptic Babylon, “the smoke of it

going up even εις τους αιωνας τως αιωνων, for ever and for ever,”6 if

there was meant merely the brief temporary desolation of Rome Pagan, in

transitu to Rome Papal? 4. What of its being afterwards the abode of all

unclean beasts and dæmons? Would Bossuet, observes Vitringa, have these

to be the Popes and Cardinals of Papal Rome? 5. Was it really Rome Pagan

that was desolated by the Goths; so as Bossuet and his followers would

have it? Surely, if there be a fact clear in history, it is this, that

it was Rome Christianized in profession, I might almost say, Rome Papal,

that was the subject of these desolations.

As this last point is one which, if proved, utterly overthrows the whole

Bossuetan or Roman-Catholic Apocalyptic Præterist Scheme, the Romanists

have been at great pains to represent the fact otherwise. So Bossuet in

his Chap. 3:12–16; and Mr. Miley too, just recently, in his Rome Pagan

and Papal. “It is well nigh a century since the triumph of the labarum,”

says the latter writer in one of his vivid sketches, with reference to

the epoch of Alaric’s first attack on Rome, “and Rome still wears the

aspect of a Pagan city:—one hundred and fifty-two temples, and one

hundred and eighty smaller shrines, are still sacred to the heathen

gods, and used for their public worship.”1 On what authority Mr. M.

makes such an assertion I know not. Bossuet takes care not quite so far

to commit himself. The facts of the case are, I believe, as follows.

Constantine did not authoritatively abolish Paganism: but he so showed

disfavour to it that it rapidly sunk into discredit in the empire; less

however at Rome than elsewhere. With Julian came a partial and

short-lived revival of Paganism; followed on his death by a reaction in

favour of Christianity. But “from that period up to the fall of the

empire a hostile sect, which regarded itself as unjustly stripped of its

ancient honours, invoked the vengeance of the gods on the heads of the

Government, exulted in the public calamities, and probably hastened them

by its intrigues.” So Sismondi, with his usual accuracy, as quoted by

Mr. Miley.2 Of this sect were various members of the Roman senate. On

Theodosius’ becoming sole emperor, i. e. emperor of the West as well as

East, one of his first measures, A.D. 392, was to forbid the worship of

idols on pain of death. At Rome, however, by a certain tacit license, or

connivance, heathen worship was still in a measure permitted: until in

394 himself visiting Rome, and finding a reluctance to abolish what

remained of Pagan rites on the part of many of the senators, Theodosius

withdrew the public funds by which they had been supported. On this the

old Pagan worship was discontinued:4 and, the Pagan temples having in

many places soon after been destroyed by the zeal of Christians, the

very fact of Pagan worship having been discontinued was given by

Honorius, the Western Emperor, as a reason for not destroying the temple

fabrics.1—Such was the state of things when Alaric first invaded Italy.

And it was only in 409, after he had begun the siege of Rome, and God’s

judgment began to be felt, that the Pagan faction or sect, spoken of by

Sismondi, stirred itself up: and raising the cry that the calamity came

in consequence of the gods of old Rome having been neglected,2 prevailed

on the authorities, including Pope Innocent himself, to sacrifice to

them in the capitol and other temples.3 But this was a comparatively

solitary act. As the judgment of the Gothic desolations went on, it was

only in secret that the worship of the heathen gods was kept up; and

this in reference to such more trivial Pagan rites, as taking auguries.4

The dominant religion, that which was alone legalized in Rome, as well

as elsewhere throughout the empire, and whose worship was alone

celebrated openly and with pomp, was the Christian religion with the

Pope as its head. Insomuch that in 450, just at the epoch of Genseric

and Attila, Pope Leo, in an address to the people of Rome on St. Peter

and St. Paul’s day, thus characterized Rome and the Roman people:—“These

are they that have advanced you to the glory of being a holy nation, a

chosen people, a priestly and royal city: so as that thou shouldest be,

through the seat of Peter, the head of the world; and with wider rule

through religion than by mere earthly domination.”5

Was it then Rome Pagan, or Rome incipiently Papal, that was the subject

of Alaric’s first attack, and of the subsequent ravages of Genseric,

Odoacer, and Totilas?1 I think the reader will agree with me that Pope

Leo himself has pretty well settled that question; and there with given

the coup de grace to Bossuet’s and Miley’s Roman Catholic Version of the

Præterist Apocalyptic Scheme.

And so I conclude my critique. In concluding, however, I must beg my

readers not to forget another and quite different absurdity that attends

the Scheme; viz. that of crowding all the magnificent Old Testament

promises of the final promised blessedness on earth into some minimum of

time after Antichrist’s destruction: one Apocalyptically not exprest at

all, according to Bossuet;2 and in Daniel only perhaps by the 45 days.

But on this it will suffice that I refer my readers to the remarks on it

of the Roman Catholic writers Père Lambert or Lacunza.

CHAPTER II

EXAMINATION OF THE FUTURISTS’ APOCALYPTIC SCHEME

The Futurists’ is the second, or rather third, grand anti-Protestant

Apocalyptic Scheme. I might perhaps have thought it sufficient to refer

the reader to Mr. Birks’ masterly Work in refutation of it,1 but for the

consideration that my own Work would be incomplete without some such

examination of this futurist Scheme, as of the Schemes preceding:

moreover that on more than one point (chiefly as regards the 6th Seal

and the Apocalyptic Beast) Mr. Birks’ own views, of some of which I have

spoken elsewhere,2 must necessarily, in my mind, have prevented his

doing full justice to the argument.—Besides which, there is otherwise

abundantly sufficient difference between us to prevent all appearance of

my trenching on his ground.

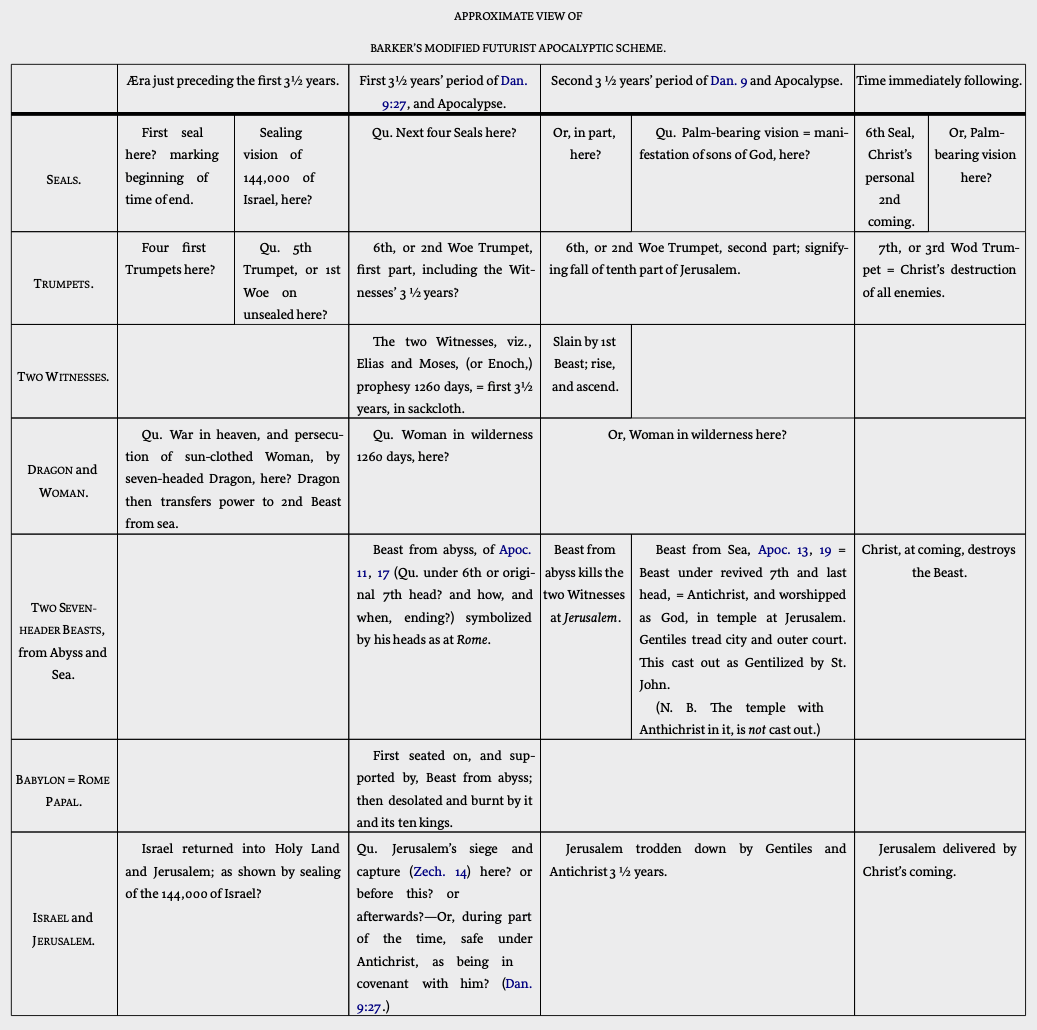

The futurist Scheme, as I have, elsewhere stated,2 was first, or nearly

first, propounded about the year 1585 by the Jesuit Ribera; as the

fittest one whereby to turn aside the Protestant application of the

Apocalyptic prophecy from the Church of Rome. In England and Ireland of

late years it has been brought into vogue chiefly by Mr. (now Dr.) S. R.

Maitland and Mr. Burgh; followed by the writer of four of the Oxford

Tracts on Antichrist.3 Its general characteristic is to view the whole

Apocalypse, at least from after the Epistles to the Seven Churches, as a

representation of the events of the consummation and second advent, all

still future: the Israel depicted in it being the literal Israel; the

temple, Apoc. 11 a literal rebuilt Jewish temple at Jerusalem; and the

Antichrist, or Apocalyptic Beast under his last head, a personal infidel

Antichrist,4 fated to reign and triumph over the saints for 3½ years,

(the days in the chronological periods being all literal days,) until

Christ’s coming shall destroy him. Of which advent of Christ, and events

immediately precursive to it, the symbols of the six first Seals are

supposed to exhibit a prefiguration singularly like what is given in

Matt. 24; and therefore strongly corroborative of the futurist view of

the Seals and the Apocalypse.—Thus, while agreeing fully with the

Præterists on the day-day principle, and partly with them as to the

literal Israel’s place in the prophecy, they are the direct antipodes of

the Præterists in their view of the time to which the main part of the

Apocalypse relates, and the person or power answering to the symbol of

the Apocalyptic Beast: the one assigning all to the long distant past,

the other to the yet distant future. And here is in fact a great

advantage that they have over the Præterists, that, instead of being in

any measure chained down by the facts of history, they can draw on the

unlimited powers of fancy, wherewith to devise in the dreamy future

whatever may seem to them to fit the sacred prophecy.

Notwithstanding this we shall, I doubt not, find abundantly sufficient

evidence in the sacred prophecy to repel and refute the crude theory;

whether in its more direct and simple form, or in any such modified form

as some writers of late have preferred to advocate. The consideration of

the latter I reserve for another Section. That of the former will be the

subject of the Section on which we are now entering.

§ 1. Original Unmodified Futurist Scheme

I purpose to discuss it with reference separately to each of the four

points just noticed as its most marked characteristics:—viz. the

supposed instant plunge of the prophecy into the far distant future of

Christ’s coming and the consummation;—the supposed parallelism of the

subjects of the Apocalyptic Seals with the successive signs specified by

Christ in his prophecy on Mount Olivet as what would precede and usher

in his coming;—the supposed literal intent of the Israel mentioned in

the Apocalyptic prophecy;—and the supposed time, place, and character of

its intended Antichrist.

I. THE SUPPOSED INSTANT PLUNGE OF THE APOCALYPTIC PROPHECY INTO

THE DISTANT FUTURE OF THE CONSUMMATION

Now, to begin, there seems here in the very idea of the thing a

something so directly contrary to all God’s previous dealings with his

people, and to all that He has himself led us to expect of Him, as to

make it all but incredible, unless some clear and direct evidence be

producible in proof of it. We read in Amos (3:7), “Surely the Lord God

will do nothing, but he revealeth his secret unto his servants the

prophets.” And of this God’s principle of action all Scripture history

is but a continued exemplification: his mode having been to give the

grand facts of prophecy in the first instance, and then, as time went

on, to furnish more and more of particulars and detail: so, gradually

but slowly, filling up prophetically that part of the original prophetic

outline in which the Church for the time being might have a special

interest; but always with the grand main point kept also in view. Thus

to Adam, after the fall, there was revealed God’s mighty purpose of the

redemption of our fallen world through the seed of the woman: to Noah,

together with declaration that this original covenanted promise was

renewed to him, the prediction of the coming judgment of the flood: to

Abraham, together with similar renewal of the grand covenant respecting

Him in whom all the families of the earth should be blessed, the more

particular prediction and promise, also, as to his natural seed becoming

a nation, and occupying Canaan: to Moses, when leading Abraham’s family,

now become a nation, from Egypt, together with reminiscence of the great

Prophet like him, that was to come, sundry predictions also about the

several tribes; and further, respecting Israel nationally, the

prediction of its apostasy from God in the course of time, and

consequent temporary casting off, captivity, and return. So too again,

long after, when the time of their first captivity drew near, together

with repetition of the same great promise, which in the interim had been

ever more and more particularly dwelt on, e. g. especially by David and

Isaiah,—I say as the time of Israel’s first captivity drew near, then

there was predicted by Jeremiah its appointed term, 70 years; and then

again, just at the close of the 70 years of that captivity, Daniel’s

memorable prophecy of there being appointed yet 70 weeks, or 490 years,

until Messiah should come, and be cut off though not for himself, and

the Jewish city and sanctuary be destroyed by a Prince that should

arise: a prophecy this last which Christ himself, after coming at the

time so defined, expanded, when speaking to his disciples on Mount

Olivet, into the full and detailed prediction of the destruction of

Jerusalem. Such, I say, had been the method pursued by God for above

4000 years, in the prophetic communications to his people, through all

the Old Testament history. And now then when the prophetic Spirit spoke

again, and for the last time, by the mouth of his apostles, more

especially of the apostle St. John, what do the Futurists contend for,

but that God’s whole system is to be supposed reversed; that in regard,

not of smaller events, or events in which the Church was but slightly

concerned, but of events in which it was essentially and most intimately

concerned, and of magnitude such as to blazon the page of each history

of Christendom, the whole 1800 years that have passed subsequently are

to be viewed as a blank in prophecy; the period having been purposely

skipped over by the Divine Spirit, in order at once to plunge the reader

into the events and times of the consummation.

The case is made stronger against them by comparing more particularly

the nearest existing parallels to the Apocalyptic prophecy in respect of

orderly arrangement, I mean the prophecies of Daniel. For we see that

they, one and all, prefigured events that were to commence immediately,

or very nearly, from the date of the vision. So in that of the symbolic

image, Dan. 2; which began its figurations with the head of gold, or

Nebuchadnezzar. So in that of the four Beasts, Dan. 7; which also began

from the Babylonian Empire then regnant. So in that of the ram and the

goat, Dan. 8, which began from the Persian Empire’s greatness; the

vision having been given just immediately before the establishment of

the Persian kingdom in power. So, once more, in Dan. 11: where the

commencement is made so regularly from the Persian Prince “Darius the

Mede,” then reigning, that it is said, “There shall stand up yet three

kings in Persia; and the fourth shall be richer than they all, and shall

stir up all against Greece;” i. e. Xerxes. Strange indeed were there in

the Apocalypse such a contrast and contrariety, as the Futurists

suppose, to all these Danielic precedents!—Moreover, the fact of its

following those precedents seems expressly declared by the revealing

Angel, at the opening of the vision in Apoc. 4, “Come up, and I will

(now) show thee what must happen μετα ταυτα, after these things.” A

statement evidently referring to Christ’s own original division of the

subjects of the revelation into “the things which St. John had first

seen,” (in the primary vision,) “the things that then were,” (viz. the

then existing state of the seven Churches,) and “the things which were

to happen after them.”—Thus our inference as to the speedy sequence of

the future first figured in the Apocalypse upon the time when the

Apocalypse was actually exhibited, seems to me not only natural, and

accordant with all the nearest Scripture precedents, but necessary. And

it both agrees with, and is confirmed by, the other divine declarations,

made alike at the first commencement and final close of the Apocalypse;

to the effect that the things predicted were quickly to come to pass,

the time of their fulfilment near at hand.

And what then the Futurists’ escape from such arguments? What the

authority for their unnatural Apocalyptic hypothesis? On the argument

from the analogy of Scripture, and specially of Daniel, no answer that I

know of has been given.1 With regard however to those statements, “To

show to his servants what must shortly come to pass,” and again, “Seal

not the sayings of this Book, for the time is at hand,” Dr. S. R.

Maitland replies that, since Christ’s coming is often said in Scripture

to be quickly,2 and the day of the Lord to be at hand,”3 albeit very far

distant, we may similarly suppose the whole subject of the Apocalyptic

predictions to be distant, though prophesied of as “shortly to come to

pass.”4 An answer little satisfactory, as it seems to me. For the

principle it goes on seems to be this;—that because two particular

cognate predictive phrases have the word quickly, or its tantamount,

attached to them, to each of which phrases a double meaning attaches,—a

lesser and a greater,—a nearer and a more distant,5—the former typical

perhaps of the latter, and this latter avowedly veiled in mystery, in

order to its being ever looked for by the Church,—that because these

have the word quickly attached in dubious sense to them, therefore

events of a quite different character, and that are altogether most

distant in time, nay and a long concatenated series of events too, may

be also so spoken of:—a principle this on which all direct meaning of

such words as quickly, or at hand, in sacred Scripture might, I

conceive, be gainsayed.—Nor indeed is it from these adverbial

expressions, insulated and alone, that the whole difficulty arises. For

we have further to observe that the events Apocalyptically prefigured to

St. John as first and next to happen in the coming future, are connected

and linked on in a very marked manner with the then actually existing

state of the seven Asiatic Churches, as the terminus à quo of all that

was to follow: it being said by the Angel, forthwith after the long and

detailed description of them in Christ’s seven dictated Epistles, to the

Churches, “Come up, and I will show thee what events are to happen after

these things;” ἁ δει γενεσθαι μετα ταυτα·—just like the defined present

terminus à quo in Dan. 11:2, “There shall stand up yet three kings in

Persia.”

But stop! Are we quite sure of our terminus? Behold the futurist critic

and expositor, as if by sleight of hand, shifts the scene itself on the

seven Asiatic Churches, which I spoke of as constituting the terminus à

quo of all that followed in the prophecy, some two thousand years, or

nearly so, forward in the world’s history. “I was in the Spirit on the

Lord’s day” (Apoc. 1:10), he explains to mean, “I was rapt by the Spirit

into the great day of the Lord.”1 And so, instead of merely contesting

the direct sequence of what was prefigured in the Apocalyptic visions of

the future, beginning Apoc. 4:1, from the definite commencing epoch of

St. John and his seven Asiatic Churches,—instead of this, I say, he

takes the bolder ground of making the great day of Christ’s coming to

judgment to be the avowed subject of all that followed St. John’s

announcement of being in the Spirit; including first and foremost, of

course, the description in the seven Epistles of the seven Churches

themselves. But how so? Is this the first mention of these Churches; so

as to leave open the idea of their being Churches non-existent until the

supposed prefigured time of the end? Assuredly not. The Apostle’s

salutation is presented to them in Apoc. 1:4, five verses prior to his

announcement of being in the Spirit, in terms just like St. Paul’s to

the then existing Churches of Thessalonica or Philippi; “John to the

seven Churches in Asia, Grace be unto you!”—Besides which who can help

being struck with the violence done by Dr. M. to the Greek original, in

construing its simple verb substantive, with the preposition in and

ablative following, “I was in the Spirit on (or in) the Lord’s day,”1 as

if it were a verb of motion, with into and an accusative following?2—Dr.

Maitland argues indeed, as “a sufficient reason” in favour of so

rendering the clause, that the Sunday, or Christian sabbath, was not in

St. John’s time, or till two centuries afterwards, called the Lord’s

day, ἡ Κυριακη ἡμερα.3 But this will be found on examination to be a

statement altogether incorrect.4 Rather it will appear that the great

day of the Lord, or judgment day, to which Dr. M. would apply it, has

never, either in the Septuagint or the New Testament, the peculiar

appellation Κυριακη attached to it, in the adjectival form; nor, I

believe, in the early Greek Fathers.1—Thus the verbal argument too is

against, not for, Dr. Maitland. The sleight of hand by which he shifts

the seven Churches, and Epistles addrest to them, into a distant future,

proves to be one that sets the sense of language, as well as the

requirements of grammar and context, at defiance. And the difficulty

remains, as it was, a millstone round the neck of the Futurist principle

of interpretation.

II. THE FUTURISTS’ IDENTIFICATION OF THE SUBJECTS OF THE

APOCALYPTIC SEALS WITH THE GOSPEL-PREACHING, WARS, FAMINES, PESTILENCES,

PERSECUTIONS, AND REVOLUTION NOTED IN CHRIST’S PROPHECY, Matt. 24, as

the precursives, they say, of his second coming

To this subject I have already briefly alluded in my Vol. i.2 And as may

be remembered, it was there shown that, while there was scarce a point

on which the asserted accordance could be made out, there was at least

one on which irreconcileable discordance could be demonstrated; and this

one so interlacing with the rest as to involve in its failure the whole

theory of Parallelism. For while, as regards the 1st Seal, it appeared

that there was nothing in its symbols to identify the rider with Christ,

or the rider’s progress on the white horse with that of

gospel-preaching,—and, as regards the 2nd Seal, the difference suggested

itself between its civil wars and the wars of nation against nation in

St. Matthew,—as regards the 3rd Seal the utter impossibility was shown